If it is split into 10 chunks, and your drive has a seek time of 8 ms, you will need to add 8 ms per chunk, plus 8 ms for the initial seek - or 90 ms - to the access time. Think of it like this: if your disk can transfer data at 20 MB per second, a 200 MB file will theoretically take 10 seconds to access/transfer if it is stored in one chunk. As such, a file in one contiguous lump will be accessed more quickly than a file in two segments, three segments, etc. Hard drives need time to seek (move their point of access to a different location) and begin culling data.

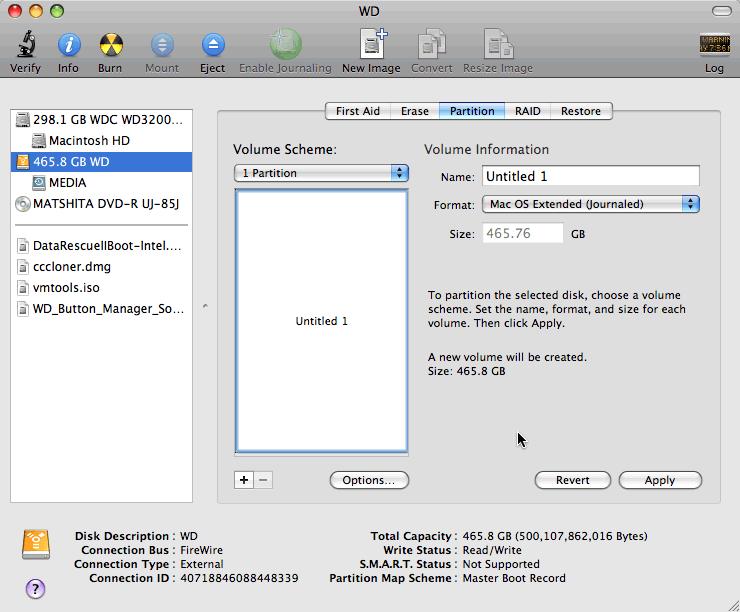

The reason the aforementioned methods work requires a quick explanation of what fragmentation is, and the difference between disk defragmentation and disk optimization:įragmentation, to put it simply, occurs when files are split up into multiple parts and stored in different locations on the hard drive. Or, you can use a utility like SuperDuper! to make a clone (or near-clone) of your startup drive, then simply format your drive using Apple's Disk Utility (located in Applications/Utilities) and copy the files back. It's somewhat tedious, but should result in faster access to said large files. In the case of myriad large files, you can easily (as described by Apple) create a backup of all your important data - essentially everything but operating system files - then re-install Mac OS X and restore the files from backup.

If these are in fact your only concerns, there are some basic remedies. You have many large files (such as digital videos).

The company states explicitly in Knowledge Base article #25668 (published in 2003) that that "you probably won't need to optimize at all if you use Mac OS X," then provides instructions for what you should do "if you think you might need to defragment."Īccording Apple's advice, there are two scenarios under which you might need to defragment your drive: Defragmentation and disk optimization in Mac OS X collectively represent an issue nearly as contentious as the debate over repairing disk permissions - one camp argues that utilties purportedly performing these functions amount to little more than nostrums, while others claim real-world performance gains as a result of the tools' usage.Īpple's input on the subject is, as usual, less than definite.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)